How to Sync Anything: Building a Sync Engine from Scratch — Part 3 posted Wednesday, April 23, 2025 by Jan Lehnardt CouchDBReplicationSyncDistsysData

Note: This is part of our series demystifying synchronisation. See our other instalments: How to Sync Anything: Introduction and How to Sync Anything: Building a Sync Engine from Scratch — Part 1 and How to Sync Anything: Building a Sync Engine from Scratch — Part 2

Last time we learned how to efficiently decide what needs syncing. This time we will learn how to version our data.

Let’s jump right in!

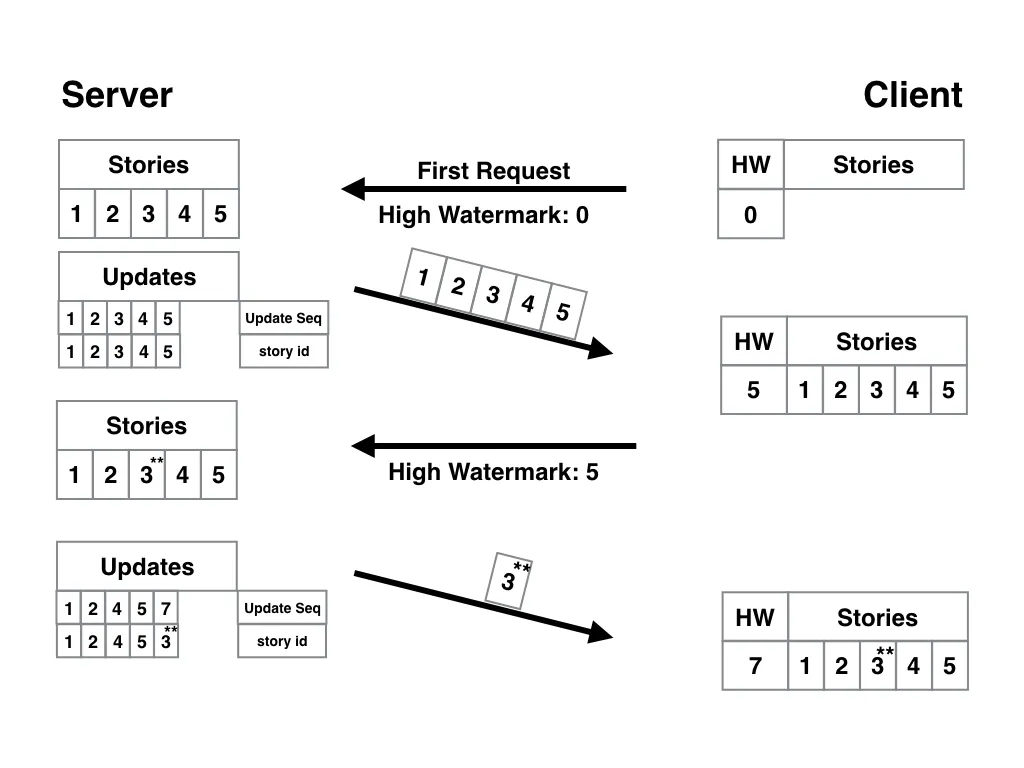

In the example from part two, with stories updating after they’ve been created, and with apps being able to request a list of current stories at any time, we already saw how to deal with different versions of a story in our calculation of a delta for an app to download.

This third part explores different version schemes and discusses their respective trade-offs. Before we go into them, let’s briefly look at what kind of technique we are looking for.

Given two objects with the same ID, we need to be able to tell which one came after the other, so we know which one is the most recent one.

If we have more than two, we need to be able to put them into an ordered list, so we know which ones come after others, and so we can know which one is the most recent, or latest. And we need to be able to tell if a more recent version of an object is an ancestor of an older one.

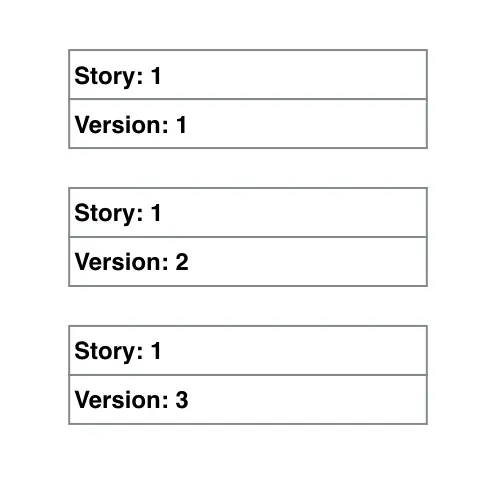

Increasing Integers

The first and most natural idea for denoting versions of a document is increasing integers. That’s just a fancy way of saying “Version 1”, “Version 2”, “Version 3”, and so on.

The advantage here is that these version numbers are very easy to understand for humans and computers alike.

So what’s the problem?

Imagine the client device and the server updating one of our story objects independently. Our story is at “Version 1”. The server then creates “Version 2” because that’s the next in the series.

The client also creates a “Version 2”, but we have no way of knowing whether the contents of the versions are the same. When we try to synchronise the client and the server now, we run into trouble.

We need to find something better to describe our versions.

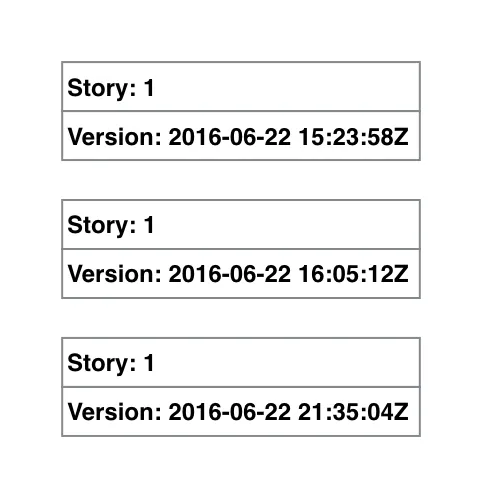

Timestamps

The next common idea for denoting versions of a document is a timestamp, a snapshot of a clock on some device, Sat Jul 23 02:16:57 2005, or 12569537329. For example, we could have story objects with a property updatedAt that we assign the timestamp of the last update to. And when we first create the object, we also record the current time.

Aside: there are many formats for timestamps with properties ranging from easy to read for humans to easy to process for computers. Whichever you choose depends on a set of tradeoffs for your application and a discussion of the merits of one format against another is outside of the scope of this article. If you just want to pick one that’s generally good, go with ISO 8601.

When we have two story objects with the same ID, we can compare their timestamps to figure out which one is the latest version of our story. As time has the convenient property of monotonically increasing, in other words: clocks only ever go forward, and this will forever be true.

Or will it? Before you go on, we’d like you to read this fantastic collection of falsehoods that programmers believe about time and the sequel. We’ll wait right here.

Hold music is playing

Say we are editing our address book on our phone. First we add a contact’s new phone number. Phone numbers are icky to type so once we are done and compare it to where they wrote it down, we see we swapped two digits.

Under the hood we recorded the current timestamp of the phone into our object versions, so we know which one was the latest. We fix the swapped digits quickly, no harm done. Or is there?

As we’ve seen in The Falsehoods, that is not always true. In fact, even companies with near infinite engineering and operations resources, like Google, can run into trouble with this.

There are a number of things that could conceivably happen, like a rogue time server telling the phone’s clock to adjust to an earlier time, or a daylight savings time switch (lucky they happen at night!); even Apple’s iPhones kept having issues with alarms set for January 1st for a while.

In our example, this means the phone number with the typo will survive as the latest edit to our object, and not the correct one. This is not what we wanted.

Whatever the exact scenario, this is plausible and has documented occurrences in small and large-scale systems: you can’t rely on timestamps to guarantee the order of two items, even if the timestamps were generated on the same device as they lead to data loss.

Ok. How can we improve on timestamps?

Before we find out, we need to introduce one more new concept: conflicts.

Embracing Conflicts

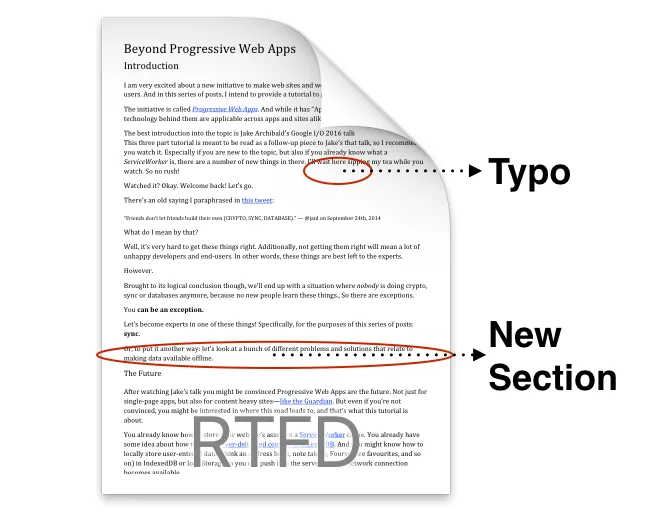

To illustrate conflicts we need to expand our example a little bit. Imagine our app is not just a consumption app for people who want to read our stories, but it is part of a content management system (CMS) where story authors can update their stories.

Our system as designed so far already works in this case; we can have the server request latest story updates from the app of all authors, and it can then send updates to any apps of our readers.

Now imagine this happening: an editor uses the CMS to edit a story by an author to fix a typo, while the author updates the same story with latest developments and we are using a timestamp to signify which version is the latest.

Even if we now have two devices with perfectly synchronised clocks (which, as we’ve learned already, we can’t guarantee we have), this shows a larger problem: what happens if two people make changes to the same object on two different devices roughly at the same time?

It doesn’t help that we know which one was updated after the other, either we pick the latest story developments and keep the typo, or vice versa. This is traditionally called a conflict.

DUN. DUN. DUN

If you are anything like me (which you are probably not, but bear with me), you don’t like the idea of conflicts. I am, as they call it, conflict averse. And while embracing conflicts might be a decent strategy in real life, in computing, we are usually trained that conflicts are bad. Very bad.

That is until we start learning about distributed systems. That’s a mighty term for a lot of ideas and concepts, but it usually boils down to: you have two or more computers connected by a network of some sort and you are trying to make it so some piece of data looks the same on both computers.

Now the tricky part is this: either computer can fail at any time, and the network can have a multitude of failure scenarios (c.f. The Fallacies of Networked Computing) that range from making the other computer appear very far away, or very busy, to turned off.

Distributed systems is a large field with a lot of applications, but that must not scare us. On the one hand, we do have a distributed system: two devices and a server, all connected over the internet.

This fits the “two or more computers connected by a network” definition. But instead of introducing a whole new field of computing into our discussion, we’ll just learn a few best practices from distributed systems and then be on our way, so no worries!

As opposed to single-machine computing, which is what we usually do, where we’ve learned that conflicts are a bad thing™, in distributed computing conflicts are a natural state of data. That doesn’t mean we can just ignore them because they are “natural”. It means we cannot ignore the fact that these things exist, or try to build up an illusion that these things don’t exist. We have to embrace conflicts.

We’ve already seen we can create a conflict, now we can look how to resolve one. Maybe in our scenario above, the typo fix is in the second paragraph and the new developments in the story are at the bottom.

If we are storing a story paragraph by paragraph, for example, we could have a conflict resolution procedure that checks if the two edits we have are in separate paragraphs, and if yes, updates our object with both new versions of the respective paragraphs and then stores the result back into our object.

This is commonly referred to as a merge. If you’ve used git or other source code version control systems (especially ones of the distributed variety), you might have seen merge strategies that do exactly that.

In this case, a computer can decide what the right final, non-conflicted version of our story is.

But now imagine both author and editor fixed the typo, but the author decided to use a different word altogether, while the editor just corrected the spelling, and both are doing this at the same time.

In that case, it is impossible for a computer to know which is the correct version. We could apply a policy in our app that in case of a conflict the author’s changes should take precedent. Or editors get the preferred treatment. Whichever it is, this can be a viable strategy for specific apps.

As mentioned before, these are all examples, and we are trying to become experts in sync more generically. So we need a better solution.

And here is a bit of a bummer: there are some types of conflicts that no computer can ever solve. We will need human intervention. There is no way around this, but at the end of the day, our brains are a lot more sophisticated than computers and conflict resolution is where this plays out.

Despite this, I hope you feel a little more comfortable with conflicts.

As an added bonus, now we are equipped to learn how to improve on timestamps for versioning our objects.

Vector Clocks

If you start searching for techniques to solve the issues with timestamps from a wall clock, you will eventually find a mention of vector clocks, for a variant, see Lampert Timestamps. A vector clock also works with timestamps — though its source is not a wall clock, like we humans use, but a so-called logical clock.

When using vector clocks as version specifiers, we not only send logical timestamps with our objects, but also the state of the logical clock, so that later, when it is time (pun intended) to compare two objects, we can calculate which one came first. Great!

Just one more thing.

Remember when we talked about the author and the editor of a story fixing a typo and adding to the story at the same time? We now know how to detect and how to resolve this conflict.

But what if the typo fix both create result in the same text? With timestamps or vector clocks, a conflict is still generated, and our subsequent merge procedure has got nothing to do. So we can handle this too, but since the resulting story is the same, wouldn’t it be nice to not create a conflict here in the first place?

I realise this example is a little bit contrived, but I hope by staying within our example project, we can see the problem here. Where the problem would actually make our lives harder is when we don’t have a single sync server, but a cluster of sync servers, which we might need for scaling to higher and higher loads of our system.

Explaining all this takes time, and this tutorial is already getting long, so we are going to skip the details of this. I hope you forgive me. If you don’t, I hope this gif of a squirrel makes up for it:

Content Addressable Versions

To solve the problem of same edits generating conflicts, we need to look at another technique: Content Addressable Versions. The idea here is this: take the contents of an object, pass it through a hash function, and use the resulting hash as the version. If we now make the same change on two devices, we don’t generate a conflict. Hooray!

We have one old problem though: Content Addressable Versions are not ordered. There is no way to take two of those versions and know from their value which came before the other. This is unfortunate, but we can solve this.

Instead of replacing the version with each object update, we keep an ordered list of versions along with the document. When we update the object, we put that Content Addressable Version at the top of the list. Then we can know which version came before another by traversing our list.

Before this is generally useful, we must add one pragmatic trade-off. If we update our objects a lot, our list of versions gets very long, and we are storing a lot of data, and moving said data across devices, and at some point we are losing all the benefits we covered when we discussed deltas above.

As a result, we make this list a bounded list, e.g., it can have at most “X” entries. We can even make this length adjustable depending on our application. Anything between 10 and 1000 is reasonable for general purpose applications, so we’ll have to play with our app to see what’s best.

The trade-off here is avoiding unnecessary conflicts at the expense of a little more storage space, and we get to decide how much storage we want to spend for this benefit.

You may think that the list of versions is rather clunky compared to a neat solution like Vector Clocks. But being able to avoid conflicts where possible becomes a priority when our server becomes a cluster of servers that all work independently to handle our application load and we want to present a consistent set of data to our users.

Storing Conflicts Efficiently

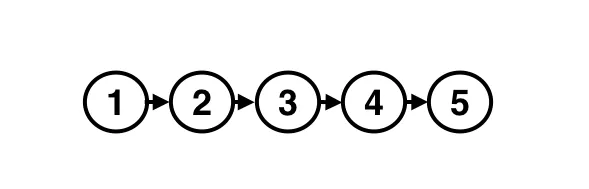

And then, finally, one last thing. When we are storing our ordered list of versions, it looks like this, simplified to use numbers instead of our Content Addressable Versions:

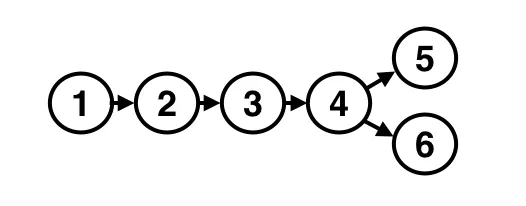

We have five versions; now we are creating a conflict. In order to signify we have two versions that are in conflict, we put them in a sub-list at the top of our list:

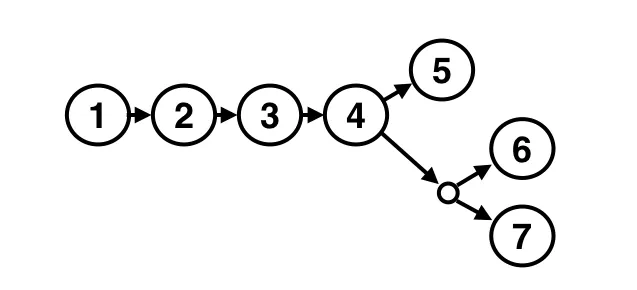

We now know that version “6” and version “5” are in conflict. Now imagine instead of resolving the conflict first, we create another one:

Now we have versions “7” and “6” in conflict, and that conflict being in conflict with version “5”. Heavy stuff!

We are representing versions in a tree structure. It allows us to:

- store conflicts efficiently, and

- resolve them recursively, so regardless of how many conflict we have, we can always get to a non-conflicted state eventually.

Putting it All Together

Here is a summary of our algorithm, without the explanation of why we do all the things, summing up all of the above:

- There are two devices, A and B, that want to sync data from A to B.

- Read high watermark checkpoints from both devices, if they exist.

- Start reading the update sequence on A from the recorded high watermark or from the beginning, if none exists.

- for each ID/version pair:

- is it a delete?

- Yes: store the delete locally (see below) on B.

- do we have the ID/version pair already locally on B?

- No: fetch ID/version from A and store it locally (see below) on B.

- store high watermark of current update sequence on A and B.

- is it a delete?

Store it Locally:

- Check version list to see if the new version is a direct successor of the currently latest version on B.

- Yes: add the new version to the data store on B.

- No: create a conflict.

Note: I’m glossing over a few details here that involve tracking of deleted conflicts, which are outside of the scope of this tutorial.

Conclusion

Thank you for reading! I hope you learned a lot about the pitfalls of synchronising data reliably and that you are not discouraged to tackle your own sync solutions based on the principles we’ve explored here.

With all the knowledge you’ve gained here, I hope you feel empowered to build your own sync engine!

Please leave any feedback in the comments on Mastodon.

Without you knowing, I explained to you the why and how of the CouchDB Replication Protocol, which allows seamless peer-to-peer data sync between any number of peers, including all the scenarios we’ve explored above.

The CouchDB Replication Protocol is implemented in CouchDB itself, so that covers our server component. Then there is the PouchDB project implementing the same protocol in JavaScript targeted at Browser and Node.js applications; that covers your clients and dev servers.

Addendum

There are two related technologies I’d be amiss to not mention: Operational Transforms and CRDTs.

Operational Transforms

If you’ve ever seen collaborative text editing on Etherpad, Google Docs, or similar, that is powered by a technology called Operational Transforms. It is designed to let any number of people collaborate on text at the same time. It can deal with a certain level of network instability, but generally, it requires clients to be connected at all times. If you go and keep editing, your changes can be integrated later, but not indefinitely later.

In addition, it is designed for text, not for generic objects, so for true offline capabilities of generic data objects, Operational Transforms are less useful. Check them out if you need a solution for mostly connected text.

CRDTs

Conflict-Free Replicated Data Types or CRDTs are specialised data structures designed for use in distributed systems and they have a lot of the properties we’ve discussed in this tutorial, but most notably, they do not have a concept of conflicts. How great is that?! Very, in fact.

Alas, everything in programming is trade-offs, so what do we trade for being able to have conflict-free data structures? Well, they are specialised data structures, like sets and counters, and not generic object representations like JSON. So, we’ll have to buy into a whole world of these specialised data structures, and maybe we have a hard time mapping our application objects to them. If you think your application can benefit from CRDTs, I strongly encourage you to try them out, but be aware of the trade-offs.

An earlier version of this post used to be published on the now defunct hood.ie blog. That earlier version had received reviews from Naomi Slater, Katharina Hößel and Jake Archibald. My thanks to them.

« Back to the blog post overview