How to Sync Anything: Building a Sync Engine from Scratch — Part 1 posted Wednesday, April 9, 2025 by Jan Lehnardt CouchDBReplicationSyncDistsysData

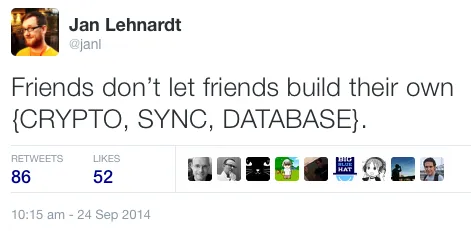

There’s an old saying I paraphrased in this by now ancient tweet[sic]:

“Friends don’t let friends build their own {CRYPTO, SYNC, DATABASE}.” — @janl on September 24th, 2014

What do I mean by that?

Note: This is part of our series demystifying synchronisation. See our other instalments: How to Sync Anything: Introduction, How to Sync Anything: Building a Sync Engine from Scratch — Part 2 and How to Sync Anything: Building a Sync Engine from Scratch — Part 3

Well, it’s very hard to get these things right. Additionally, not getting them right will mean a lot of unhappy developers and end-users. In other words, these things are best left to the experts.

However.

Brought to its logical conclusion, we’ll end up with a situation where nobody is doing crypto, sync or databases anymore, because no new people learn these things. So there are exceptions.

You can be an exception.

Let’s become experts in one of these things! Specifically, for the purposes of this series of posts: sync.

Or, to put it another way: let’s look at a bunch of different problems and solutions that relate to making data available offline.

I’m picking a specific field (web frontend / backend sync) by way of example, but know that the same concepts apply to any two or more sites you want to synchronise.

The Future

When I first wrote this article, Progressive Web Apps (PWAs) were just being announced as maybe becoming a thing in the future.

That future has long since arrived. What has not arrived is the logical next step that comes after caching your static assets: how to make your data available when a web app is not connected to a server.

You already know how to store your website’s assets in a ServiceWorker cache. You already have some idea about how to store server-delivered content in IndexedDB. And you might know how to locally store user-entered data (think an address book, note taking, favourites, and so on) in IndexedDB or localStorage so you can push it to the server when a network connection becomes available.

We can already see a few different scenarios:

- server always pushes (news)

- client always pushes (notes)

- both push (social, email, or multi-device access of individual notes, and all forms of group data sharing.)

Let’s have a look at the different techniques required to make this all work. We’ll see which applies to which use-case while we go through everything, step-by-step.

The Scene: Background Sync

In his introductory talk about PWAs, Jake Archibald shows an example of a chat application. Towards the end, he uses the Background Sync API to send new messages “later”, whenever the browser thinks it has an actual internet connection (as opposed to having a network but not thinking there’s an internet connection).

This is a great UX experience: the interaction is done as far as the user is concerned. There is still an indicator that the message hasn’t reached the recipient yet, but there is no need to keep the user waiting for any network operations.

In the same talk, Jake explained that the browser (and sometimes mobile operating system) mechanics that determine whether a device is online are not very useful. That’s because they only cover the connection from the device to the wifi router or cell tower. But there are a lot of steps between there and the final web server. For example: ISP routers, transparent proxies, satellite uplinks, just to name a few.

Now imagine we are sending a message within a Background Sync event as shown in Jake’s talk, but we’re on a fast train that goes through a bunch of tunnels in fast succession. Or we are on a conference or hotel wifi. Or we’re a large event with thousands of other people.

Our phone might get a request/response going, and as a result, wakes up Background Sync and tries to send our message. But by the time the message gets sent, we don’t get any requests going because the network became unavailable again. Background Sync will then re-try at a later time. Which is great, and exactly what we want. We don’t have to worry about whether the message is sent, because we know it will be, eventually.

Now. Let’s look behind the scenes.

The Cycle of (the) Web

Even though there are many hops at which things can go wrong in a HTTP request/response cycle, there are generally two parts: the request and the response.

Each part can fail, so we have to account for the following scenarios:

- the request fails

- the request makes it, but the response fails

Scenario one is neatly covered by Background Sync, but what about scenario two?

Imagine we are sending a message. The server accepts it and sends it onwards to the final recipient. Then, the server responds to the device, saying it handled the message correctly.

If that response fails, Background Sync will consider the message sending request as failed and will re-try it later. At that time, the server accepts the message and sends it to the recipient again. And now we’ve created a mess, because the recipient is left wondering why there are two messages that are exactly the same.

And if we are really unlucky, our recipient will get an infinite stream of the same message because the same problem is happening over and over and over again.

Let’s see how we can avoid this.

There are solutions for this exact problem that we can employ in the server portion of our app. But we’ll get to that later. For now, let’s look at how to solve this more generically, so that we can solve the same problem when it comes up in very different contexts, not just when sending messages.

Identity

In programming, we generally work with bits of data wrapped up in objects. If we want to be able to refer to an object at a later time, we must be able to reference it unambiguously. Sometimes that means giving something a name (like an auto incrementing number) and sometimes we can derive an identity from a number of uniquely identifying properties of the object.

For example: in an address book, assuming no two people have the same name (a bad assumption, but we’ll get to this shortly), the identity (or ID) of an object could be derived from the combination of the first name and the last name. That would be an example of what is known in database circles as a natural key.

The advantage of a natural key is that you don’t need to store any extra data on the object to be able to refer to it later. It also means your data is easier to de-duplicate.

Natural Key Disadvantages

There are two disadvantages to using natural keys: changes in the natural key and the need for uniqueness.

Key Changes

Say your natural key is somebody’s email address. Email addresses change, and you need to be able to deal with this change.

For example, if you update someone’s email address, but another object was using that as the natural key to refer to your object, that second object will need to update its reference.

While this type of change might be infrequent, other natural keys can change more frequently.

This is opposed to an opaque key, or surrogate key, that is a number (like an account number, a social security number, a phone number) or string of random characters (e.g. a UUID). Every time you’ve seen an auto incrementing ID column in an SQL database, that is a surrogate key.

Uniqueness

In our address book example, when your natural key is derived from last name and the first name, we may hit a problem. What if you know two people named Jane Smith? Our natural key is not unique, so if we try to look up “Jane Smith”, we can’t be sure which object to return.

Surrogate Key Advantages

Surrogate keys have the advantage of being agnostic to any changes in our objects’ data.

The disadvantage is that they are opaque, so there’s no natural relationship between an object’s ID and its data. The ID 43135 doesn’t tell you a whole lot about a user record for Jane Smith.

While these IDs are usually only used by computers, sometimes they leak out into the real world. Sometimes we even expect people to remember them and manipulate them. Not ideal. In addition, they make debugging and logging harder, as devs are now forced to map IDs to objects’ natural data to see anything useful.

Moving Forwards

Since we are looking at how to make data available offline, and since that means storing data on an end-user device and a server, we have multiple copies of all our data. So we need to be sure that any operations can unambiguously reference that data.

So, when creating a new object that we give it a unique ID. And we can’t guarantee this with natural keys. A new Jane Smith could be added on the server and the user’s device while they can’t talk to each other because one is offline. That would spell all sorts of trouble for us.

Unless any of our data lends itself to be a natural key without the disadvantages, we use surrogate keys.

Specifically we use UUIDs, because they have the convenient property that even though you still can’t guarantee the uniqueness of natural data on disconnected devices, the chance of assigning the same UUID to different objects on two or more devices is so unlikely, we practically don’t even have to consider it a possibility.

With that sorted, we have a new problem. We have multiple sets of data, which may or may not diverge from each other in various ways. In my next post, I’ll show you how to figure out what’s changed, what needs syncing, and in what direction.

This concludes part 1 of our series “Beyond Progressive Web Apps”. Stay tuned for part 2: “We need to know what’s new”.

An earlier version of this post used to be published on the now defunct hood.ie blog. That earlier version had received reviews from Naomi Slater, Katharina Hößel and Jake Archibald. My thanks to them.

« Back to the blog post overview