How to Sync Anything: Building a Sync Engine from Scratch — Part 2 posted Wednesday, April 16, 2025 by Jan Lehnardt CouchDBReplicationSyncDistsysData

Note: This is part of our series demystifying synchronisation. See our other instalments: How to Sync Anything: Introduction, How to Sync Anything: Building a Sync Engine from Scratch — Part 1 and How to Sync Anything: Building a Sync Engine from Scratch — Part 3

In this part, we will learn how to efficiently find out what data needs to be synchronised.

Say we have a news app that runs on mobile devices and a server that publishes new stories. Blogs and RSS are good real-world examples.

The scenario is this: our app starts for the first time and there are no stories available for the user to read on the device. So, the app asks the server to send the latest set of stories to the device. End result: our users get to read some stories.

Later, when our apps starts for the second time, your app asks for the latest set of stories.

And here is the first interesting bit: we don’t want to send the app the stories it already has.

Why?

Four reasons:

- They are already on the device, so it’s redundant

- It costs us server processing time

- It costs our users bandwidth

- It adds response-time latency to the experience

As a general rule of thumb, in user experience design: don’t let the user wait unnecessarily or they will get frustrated and stop using your app, your store, whatever.

So what’s the solution?

We need to request new stories from the server in a way that says “I’ve got all stories up to this point. Give, give me anything that’s new”.

We’ll call the difference between “all stories” and “stories that exist on the client” the delta (i.e. difference).

The delta is what we need to get from the server.

Calculating the Delta

To ask for the delta efficiently, we need two ingredients:

- Our app needs to store its state somewhere, so it knows what stories it already has. We’ll call this the high watermark (for reasons that will become clear soon). In a native app, this could be stored in a device-local database or file. In a website or web app, this could live in browser storage systems like localStorage, or IndexedDB.

- Our server needs to look up the list of all stories, sorted by when they were published. It needs to be able to do do this efficiently. And it needs to be able to send back any range of stories, from any specified start date to the present moment.

A naive implementation on the server side would be something equivalent to retrieving all stories from the database, sorting them by date in memory, before sending the result to the app. If the app sends a high watermark, the server would only send stories that come after the high watermark.

While this definitely works, it is not very efficient.

All stories have to be loaded from the database, sorted and finally filtered to match the range the client is interested in.

While a server with only a few apps requesting only a handful of stories can easily do this, we should be looking for optimisations here. Something that will work with large data sets.

How? Traditionally, we would add an index to the database.

The Index

An index has two things going for it:

-

Order: things will be stored in index order on disk, so reading things (e.g. stories sorted by publish date) in that order is very efficient.

-

Support for ranges: reading only part of an index from any point in the index range (e.g. all stories after a certain date) is very efficient.

Maybe the database already has an auto-increment integer as a primary key. If so, each new story gets an ID integer that is one higher the previous ID.

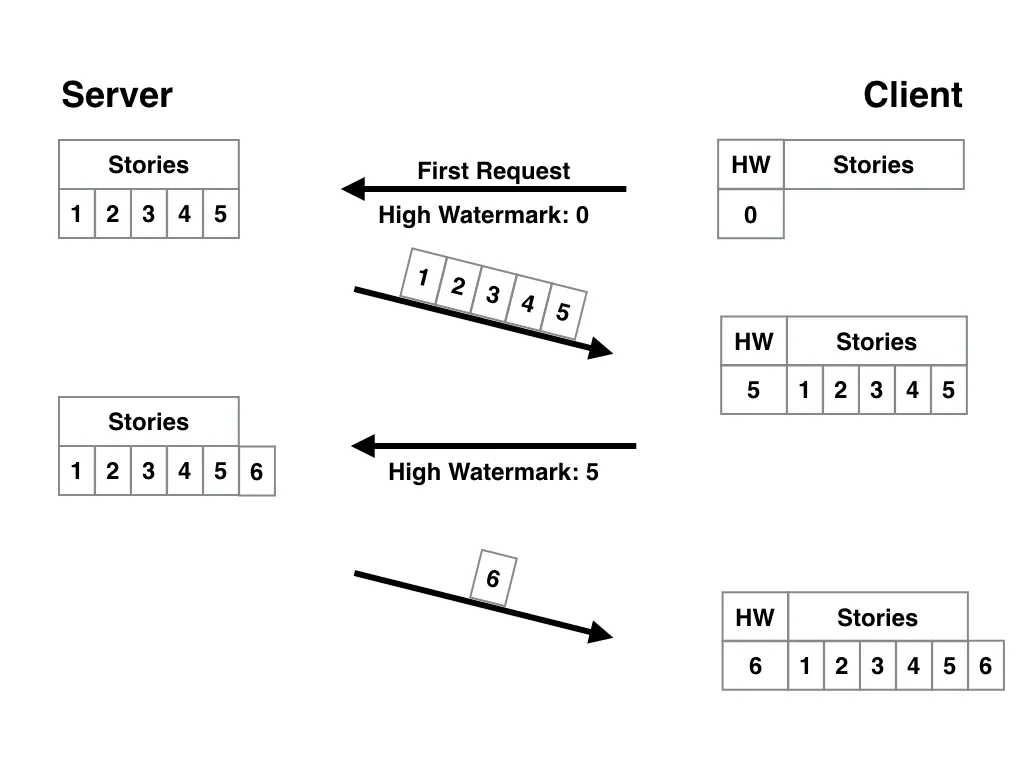

If this is the case, the server is already prepared and the app only needs to store the highest ID it gets from the server in the initial request. The app can then send that ID as the high watermark for subsequent requests.

When the app receives the new batch of stories, it stores the new highest ID as the next high watermark, and so on.

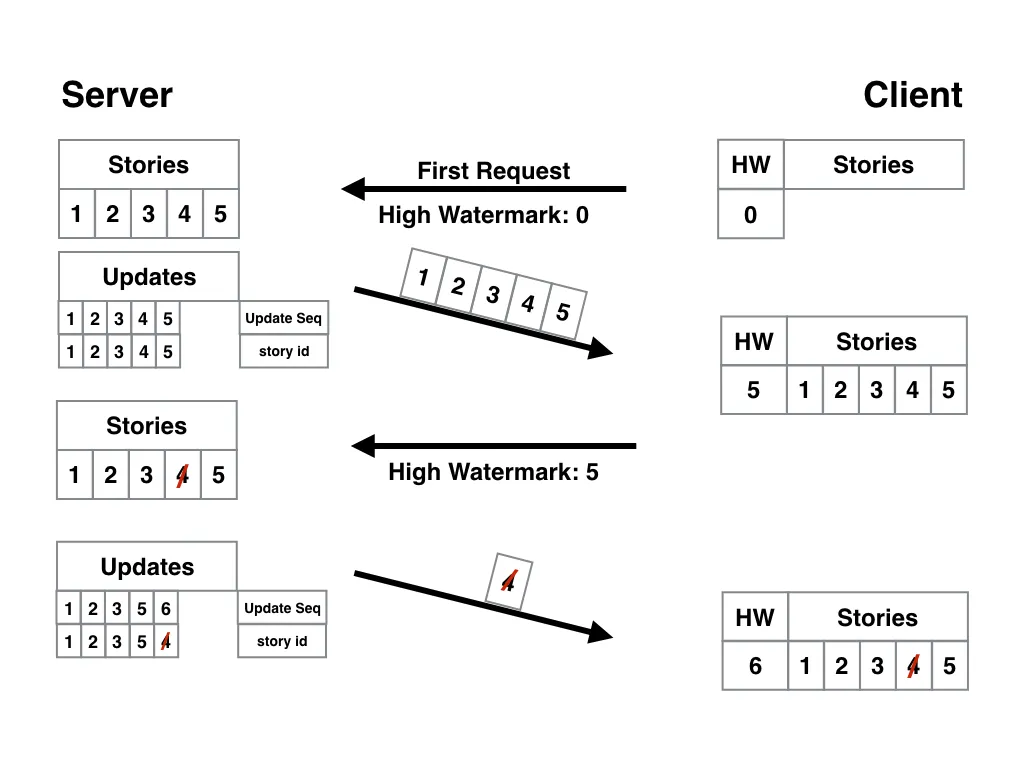

Here’s what this looks like:

Updates

Now, let’s imagine our stories are sometimes updated. This is fairly common. Typos need to be fixed, corrections posted, new story developments need to be added, and so on.

In this case, using an auto-incrementing ID is not a good solution.

Not only do new stories need to get a new ID, or more precisely a higher ID, but also: updates to a story need to get a higher ID, so that they are included in the calculation of the next delta.

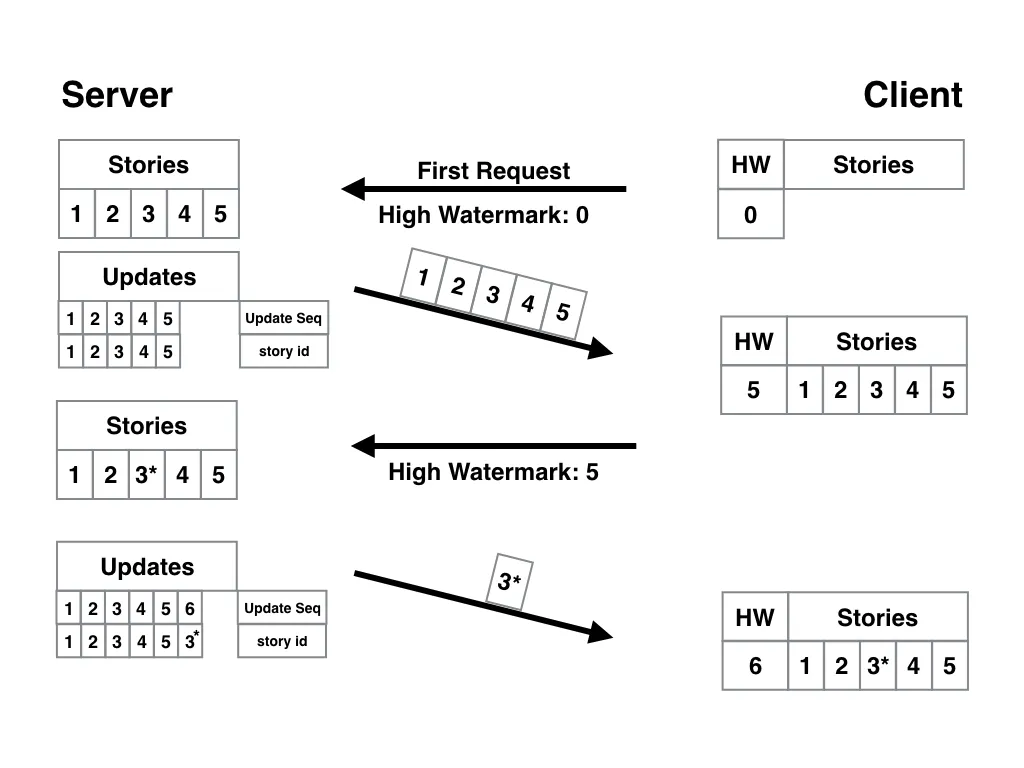

To solve this, we need a new table: updates.

This updates table provides a secondary index that we use for recording updates only. If you add one record for every update, pointing back to the corresponding story that was updated, the auto-incrementing ID functions as an update sequence.

Now, instead of passing back the story ID as a high watermark, the client can pass back the last update sequence it got. (We have to tell the client the latest update sequence with every request for this to work.)

When the server receives an update sequence from the client as the high watermark, all it needs to do is send back every story that corresponds to every update with a higher update sequence ID in the updates table.

In this example, the client first receives five stories and the update sequence ID of “5”. When the client sends the “5” back as the high watermark, the server notices that there’s an update record with ID “6” and sends back the only the corresponding story, which happens to be the story with ID “3”. The client also now gets the update sequence “6”, which is recorded locally as the high watermark.

In our case, our app might choose to handle this information by adding an “updated” marker to the list of stories, so our user knows the story has been updated with new information, even if it was previously read.

So far so good!

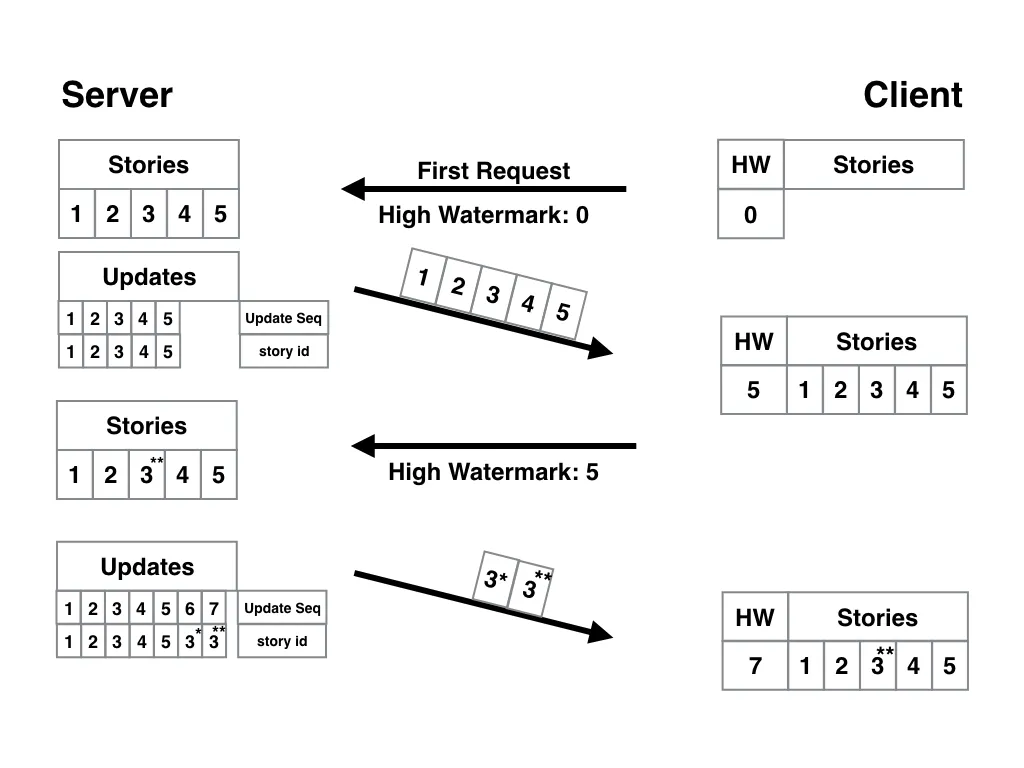

But we need to handle one more case for updates: what happens when a story has been updated twice?

This is how it would look in our current system:

This looks very similar to the previous image, with one difference: the delta includes story three twice. Thing is, we only really need the latest update. That previous update will be discarded by the client, so we’re wasting server resources, bandwidth, and UX latency sending it.

In our example scenario, this isn’t too bad. But imagine we’re downloading thousands of objects with hundreds of updates.

Not great.

So what do we do about it?

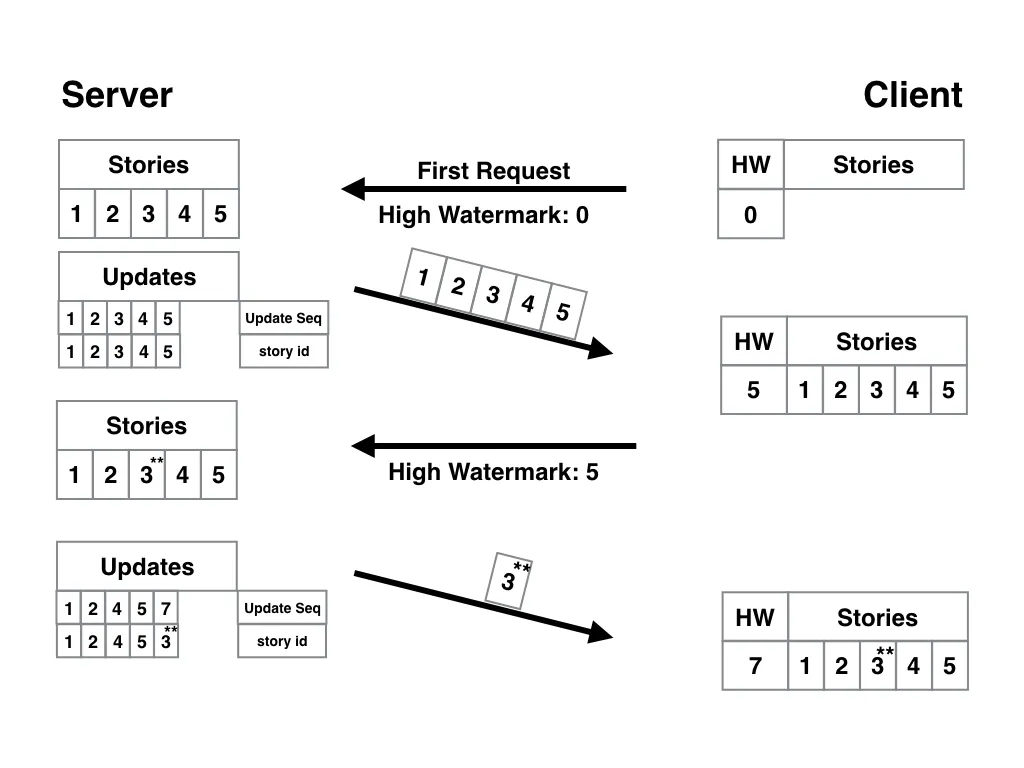

The update sequence index we’re using is called a composite index. This means more than one data item defines the index range and how it is sorted. In our case, we have an auto-increasing change ID plus a static story ID.

We need to make one more change to our composite index to solve this multiple update problem.

Let’s make it so that the story ID column in the updates table is unique. Every time we try to write to that table, if we see there’s an existing entry with the story ID we’re about to record a change for, we delete the old row.

If we do this, there will only ever be one update record per story, and it will always correspond to the latest update.

Here’s what that looks like:

What happened here?

Between the first and second requests, two changes were made to story three. Because the story ID column on the updates table is unique, we only have the final update recorded, which is why the update with ID “6” is missing.

The end result? Our client only receives the final update for story three.

Deletes

There’s one last thing before we move on: deletes.

In our app, we want to treat deletes as updates, so that deletes can be sent to the client like any other sort of change.

Let’s take the same example we’ve already been using and instead imagine that between the first and second client requests, story four is deleted from the server.

In this case, we’d want to record this deletion in the updates table, along with an update ID. We can then send this information back to the client as if it were a new story, updating the high watermark as we do so.

Here’s what that would look like:

At this point, the app has several choices. The simplest is probably just to delete the story locally.

The Road to CRUD

Congratulations! Now we know how to communicate new stories, story updates, and story deletions to our app. In other words, we can sync Create, Read, Update, and Delete (CRUD) operations.

And here’s a cool thing: we’ve done this generically enough that a story can be any sort of object we might want.

In this post, we’ve spoken about different versions of the same object. For example, using 3, 3*, and 3** to refer to the first, second, and third versions of story three. We’re also talking about versions when we talk about the deleted and non-deleted version of story 4.

This concept — versions — is very important. So we’ll take a closer look at that in post three of this three part miniseries.

An earlier version of this post used to be published on the now defunct hood.ie blog. That earlier version had received reviews from Naomi Slater, Katharina Hößel and Jake Archibald, tef, and James. My thanks to them.

« Back to the blog post overview